On a frigid Chicago day in December of 1928, Philip K. Dick was born twenty minutes ahead of his sister Jane. The twins, the boy with blonde hair and the girl with dark hair, were six weeks premature, and the inexperienced parents, Edgar Dick and Dorothy Hudner, were in over their heads. The twins struggled to gain weight. Jane was born weighing just three and a half pounds and suffered what at the time was termed “failure to thrive.” Dorothy didn’t have enough milk and couldn’t seem to figure out the right formula. Edgar had retreated to the local men’s club to avoid the babies’ incessant crying.

A little over a month later when a nurse and doctor came to visit the family, Philip weighed two and a half pounds and Jane only two and a quarter, according to Edgar, who, like his son, seems prone to hyperbole. The twins were rushed to the hospital in a heated incubator. Jane died on the car ride there.

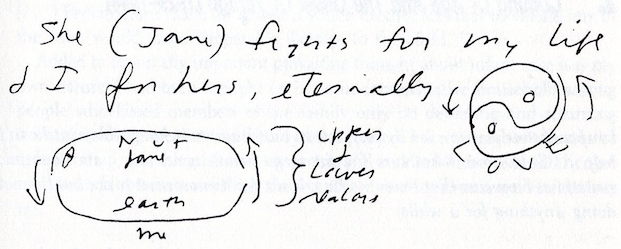

The tragic episode became the emotional centerpiece in Dick’s life. Fifty years later the eccentric science fiction author wrote in his Exegesis, a gargantuan set of notes Dick made about what he termed his ‘mystical experiences’ in the 1970s, “My sister is everything to me. I am damned always to be separated from her and with her, in an oscillation.”

Philip K. Dick, who died in 1982, is already the most adapted science fiction writer in Hollywood with more than a dozen films and series made of his work including Blade Runner, Minority Report, Total Recall, and Amazon’s Philip K Dick’s Electric Dreams and The Man in the High Castle.

Now there are two Dick-centric biopics currently in the Hollywood pipeline, both set to feature Dick’s twin. News broke in July that Children of Men director Alfonso Cuaron and Fury Road star Charlize Theron have teamed up to produce an Amazon project titled Jane. The plot is described as “a moving, suspenseful and darkly humorous story about a woman’s unique relationship with her brilliant, but troubled twin, who also happens to be the celebrated novelist Philip K. Dick. While attempting to rescue her brother from predicaments both real and imagined, Jane plunges deeper and deeper into a fascinating world of his creation.”

Dick’s daughter, Isa Dick-Hackett, who garnered critical and commercial success as a producer on The Man in the High Castle, said of the project, “The story of Jane has been with me for as long as I can remember […] Jane, my father’s twin sister who died a few weeks after birth, was at the center of his universe. Befitting a man of his unique imagination, this film will defy the conventions of a biopic and embrace the alternate reality Philip K. Dick so desperately desired—one in which his beloved sister survived beyond six weeks of age. It is her story we will tell, her lens through which we will see him and his imagination. There is no better way to honor him than to grant him his wish, if only for the screen.”

The Jane announcement came just a few weeks after news of another bio-pic project, this one based on Paul Williams’ book, Only Apparently Real, which consists of interviews and ephemera related to his Rolling Stone article about Dick in the 1970s that helped cement Dick’s reputation as a countercultural hero, part Isaac Asimov, part Hunter S. Thompson.

The Hollywood Reporter writes, “Only Apparently Real centers on a break-in at Dick’s house that took place in the early ’70s. He was in the midst of his fourth divorce, trying to give up amphetamines, battling writer’s block and possibly being spied on by the United States government. Then his house was ransacked, his safe blown open and his manuscripts were stolen. But then again, maybe they weren’t and maybe there was never a break-in.”

The description continues, “The story also tackles what Dick himself described as a tragic theme that pervaded his life: the death in infancy of his twin sister, Jane, and the reenactment of it over and over again. Dick attributed many of his psychological issues and personal life challenges to her death, including his attachment anxieties.”

Deja Vu All Over Again

But these are not the first Hollywood projects to tackle Phil Dick’s weird personal life. In 2006, Dick’s estate, headed by daughter Isa, was reportedly developing a biopic project titled The Owl in Daylight, which wove the author’s biography with ideas from a novel he was planning at the time of his death. Tony Grisoni, who worked with Terry Gilliam on the screenplay for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, was brought in to write a script, and Paul Giamatti was slated to play Dick. While fans had high hopes, the project appears to have died in the shadows.

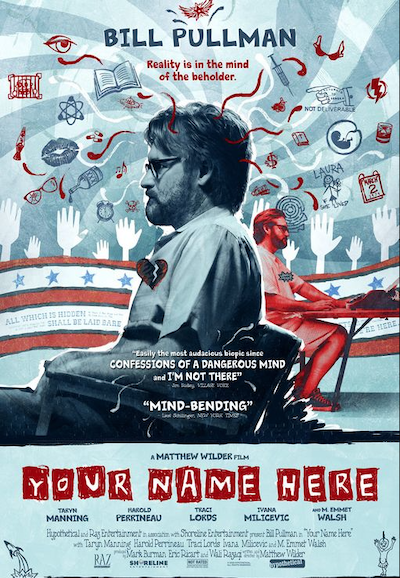

A much lower budget arthouse film from writer/director Matthew Wilder titled Your Name Here was released in 2008 just widely enough to be panned, The Hollywood Reporter saying the film “ultimately proves too impenetrable for its own good.”

Despite the critics, there are a few real gems in the movie. Bill Pullman’s performance as William J. Frick, an increasingly unhinged science fiction author desperate for answers, manages to capture some of Dick’s essential qualities as an unlikely prophet. Traci Lords plays Frick’s caustic ex-wife whose paint-peeling tirades needle Pullman’s schlubby Frick. At the film’s climax, an institutionalized Frick, tormented by ex-wives in search of alimony and trapped at the center of a malevolent conspiracy, lies on a cot in his hospital robe when he hears a child’s voice singing from the drawer of his nightstand.

In an absolutely jaw-dropping reveal, Frick opens the drawer to reveal a small mucus-covered infant. Pullman’s heartrending tenderness and relief make it one of the only emotionally relevant moments in the movie—but boy it’s a doozy. Eventually his infant sister (named Laura in the film) tells Frick he was too hard on their mother and the two inexplicably slip out of the asylum and end up eating rocky road ice cream together. Laura’s placid calm ultimately helps Frick get a grip. The cinematic moment’s strange combination of surreal absurdity and well-earned sentimentality feels closer to the vibe of Dick’s fiction than pretty much any of the other adaptations of his fiction.

Twinless Twins

Other prominent artists who survived their twins include artist Diego Rivera, playwright Thorton Wilder, and musicians Elvis and Liberace. In a 2012 newsletter published by the Twinless Twins Support Group, Dr Peter O. Whitmer writes,

“Each of these artists and also many twinless twins whose loss comes as an adult have demonstrated an unusual ability and drive – the twinning motif. Their careers are dominated by a compulsion to bring together different strands of creativity, and render something completely new. By doing this, they are attempting – for a lifetime – to seek a more fuller understanding of why they lived while their twin died. It is their attempt to replicate, in life, what can only be accomplished in death. Ultimately their life’s most profound driving force is toward becoming reunited with their dead twin.”

Elvis’ brother, Jesse Garon Presley, was stillborn thirty minutes before his twin. Presley was haunted by the death of his twin, and referred to his dead brother as his “original bodyguard.” Whitmer writes, “Elvis sought communion and re-union with the twin, sensing that the dead brother was a spiritual guide who directed him to search for meaning in life. He did this through meditation, numerology, compulsive study of both the Bible and numerous other spiritual tracts and, ultimately, through drug use.”

Similarly, Dick’s connection to his twin left him feeling divided between the world of the living and the world of the dead, and in his fiction this “twinning motif” often attempted to bridge the two worlds.

Twins in Dick’s Fiction

In his 1966 novel The Crack in Space, the orbiting brothel known as Golden Doors of Bliss is owned by a pair of conjoined twins named George Walt who share a single head. Dick writes, “They were a form of mutated twinning, joined at the base of the skull so that a single cephalic structure served both separate bodies. Evidently the personality George inhabited one hemisphere of the brain, made use of one eye: the right, as he recalled. And the personality Walt existed on the other side, distinct with its own idiosyncrasies, views and drives — and its own eye from which to view the outside universe.”

Later in the book one of the twins is killed. Dick describes the agonizing existence of the survivor, writing, “With immense difficulty the living body struggled to its feet; now its silent companion flopped against it and in horror it pushed the burdening lifeless sack away.”

In Dick’s 1965 novel, Dr. Bloodmoney, set in a radioactive post-apocalyptic Bay Area, seven-year-old Edie Keller communicates telepathically with her vestigial twin, Bill, who, roughly the size of small rabbit, lives near Edie’s appendix. The pair’s private conversations evoke an intense intimacy as well as revealing Bill’s desire to see the world of the living. Dick writes,

“I wish I could come out,” Bill said plaintively. “I wish I could be born like everybody else. Can’t I be born later on?”

In the 1974 novel, Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said, protagonist Felix Buckman, the book’s titular cop, has a psychotic break after his sister, Alys Buckman—a bisexual leather queen who binges on direct brain-stimulus at orgies—dies of an overdose of KR-3, a mysterious time-binding drug.

As Dick attempted to work out his strange religious experiences in the early 70s in his Exegesis, he wove Jane into his ever-expanding mythology. In his semi-autobiographical novel VALIS (1980), Dick develops the idea of a “two-source cosmology” with a fractured unity at its center. In the Tractates Cryptica Scriptura, a series of dense cosmological hypotheses at the conclusion of VALIS, Dick posits a “syzygy” or “pair of connected or corresponding things” at the very center of creation. Passage No. 32 reads:

“The changing information that we experience as world is an unfolding narrative. It tells about the death of a woman. This woman, who died long ago, was one of the primordial twins. She was half the divine syzygy. The purpose of the narrative is the recollection of her and her death. The Mind does not wish to forget her. Thus the ratiocination of the Brain consists of a permanent record of her existence, and, if read, will be understood this way. All the information processed by the Brain — experienced by us as the arranging and rearranging of physical objects — is an attempt at this preservation of her; stones and rocks and sticks and amoebae are traces of her. The record of her existence and passing is ordered onto the meanest level of reality by the suffering Mind which is now alone.”

Dick and His Twin

The tragic death of his twin wasn’t just fodder for Dick’s fiction. In Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick, biographer Lawrence Sutin writes, “The trauma of Jane’s death remained the central event in Phil’s psychic life. The torment extended throughout his life, manifesting itself in difficult relationships with women and a fascination with resolving dualist (twin-poled) dilemmas—SF/mainstream, real/fake, human/android, and at last (in as near an integration of intellect and emotion as Phil ever achieved) in the two-source cosmology described in his masterwork Valis (1981).”

The most obvious collateral damage from the death was Dick’s relationship with his mother whom he resented deeply for her perceived neglect. Paul Williams captured some of Dick’s harshest vitriol towards his mother. In a 1974 interview included in Only Apparently Real, Dick told Williams, “I get very angry when I think about my sister […] That she died of neglect and starvation. […] I feel my mother let her die. And I feel that I would have too — I know I would have died too, if it hadn’t been for a routine inspection by a visiting Cook County health nurse who happened to notice that both babies were dying and told my mother they had to be taken to the hospital immediately. But it was too late for my sister. […] ‘Cause I was a very lonely child and I would have loved to have my younger sister with me, all these years.”

This perceived maternal neglect, exacerbated by his mother’s hands-off parenting style with Phil which, based on much of the ‘science’ at the time, counseled limited physical contact and warned against any demonstrative affection, gave rise to a recurring figure/trope in Dick’s fiction of the cold, emotionless, and calculating woman. Here lies the inspiration for Dick’s androids: not the steel robots of the pulp science fiction he grew up on, but the emotional disconnect which obscured Dick’s suffering from the people around him. Rachel Rosen, the android fatale in Dick’s 1969 novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is only the most obvious example. In the novel, Rachel is completely unable to give or receive any kind of real love or affection.

While Dick’s preoccupation with breasts is fairly well established, it’s possible his obsession involved more than mere titillation, especially when considering that his mother was unable to produce enough milk to nourish her children. Many of Dick’s coldest female characters are described as flat chested or boyish. When Rachel Rosen strips for Rick Deckard as part of her predatory seduction, Deckard describes her body: “Rachel’s proportions, he noticed once again, were odd; with her mass of dark hair, her head seemed large, and because of her diminutive breasts, her body assumed a lank, almost childlike stance.”

Despite his bitter resentment, Dick was close with his mother throughout his life, until her death in 1978. Sutin writes, “The relationship between Phil and his mother, in its painful duality of extreme, dependent closeness and rage over errors and omissions in loving, was mirrored in every love relationship Phil ever had with a woman.”

Dorothy’s desire to treat young Philip, as she called him, like an adult went so far as to talk with him about Jane’s death at a very early age, even, according to Dick, going so far as to show him a lock of Jane’s hair. His lost sibling took on a vivid life of its own in the young boy’s fertile imagination.

When Dick was five, Dorothy and Edgar divorced after more than a year’s separation, their marriage shattered by a combination of Jane’s death and general incompatibility. Edgar moved away where he, too, grew even larger in his young son’s imagination.

Dick was an anxious child who suffered from asthma, agoraphobia, and difficulty swallowing. He was regularly absent from school, and was eventually shipped off to boarding school in Ojai, California. Dick struggled with anxiety and agoraphobia for the rest of his life.

Dick’s relationship with his sister influenced his relationships with women. Sutin quotes Kirsten Nelson (the then-current wife of friend Ray Nelson whose story “Eight O’Clock in the Morning” was eventually made into John Carpenter’s classic movie They Live), a woman Dick fell in love with in the mid-sixties, as saying, “I don’t know that he fell in love with me so much as he kind of adopted me. I think he cast me in the role of his dead sister. He felt he had to watch out for me.”

In his love life Dick perpetually sought out what he referred to as the “dark-haired girl.” His desire to love and to be loved by women was overwhelming to all involved in most cases, with a string of five tumultuous marriages to attest to the intensity of his romantic quest.

During what he termed his “mystical experiences” in the 1970s, Dick believed himself to be in contact with Aphrodite and other divine feminine entities (who often spoke in what Dick described as an “AI” voice). As Sutin writes, these included “Saint Sophia and his twin sister Jane with whom Phil felt he was, at times, in telepathic contact with.”

Philip K. Dick was finally reunited with his sister. After his death following a stroke in 1982, Dick’s remains were buried beside Jane’s in Fort Collins, Colorado. The pair share a single headstone.

So it’s by no means a stretch to use Dick’s twin sister as a lens through which to examine his life. While we don’t have many details about these bio-pics, one fairly safe bet is that Jane will be gay. This was one of Dick’s running jokes, and, I think, something he truly believed about his sister. According to ex-wife Anne Dick, in her memoir The Search for Philip K. Dick, early on in their relationship,

“Phil told me about his twin sister who had died three weeks after birth — how he still felt guilty about it. He felt that somehow he carried his twin sister inside of him. ‘And she’s a lesbian,’ he told me very seriously.”

The focus of the biopics on the tragic episode, and the desire to make a bold and ambitious piece of art out of the pain and wonder of the experience and to explore its emotional legacy is indeed a fitting tribute to Philip K. Dick’s life, work, and the undying love he felt for his sister.

David Gill has studied the life and work of Philip K. Dick for more than twenty years. He teaches writing and literature at San Francisco State University. He has written about Dick extensively for his blog, Total Dick-Head, and worked on the footnotes for Dick’s Exegesis (the notes the science fiction author made regarding his ‘mystical experiences’ in the 1970s) published in 2011. He lives in Oakland with his wife, family, and cats.. Follow David Gill on Twitter at: @saxum_paternus and Instagram at: @songotaku.

The further we travel into the Twenty First century the greater my appreciation of Philip K. Dick becomes. What stands out about his fiction is how increasingly realistic it seems. It’s not surprising his own sad life resembled a Philip K. Dick novel, but now the whole world also seems to. I’m delighted contemporary film makers are exploring Dick’s life and philosophy. I think that’s more likely to produce a fitting tribute to his unique imagination than most of the mostly mediocre cinematic adaptations of his work so far. (A Scanner Darkly being the honorable exception.)

Great article by one of the best PKD experts around!